Claire Poelking, Program Associate in Conservation and Sustainable Development, writes about work to create resilient, climate-adaptive landscapes to mitigate harm from extreme climate events.

Stepping outside the MacArthur Foundation office on the corner of Dearborn and Adams in downtown Chicago, you are met with a 53-foot-tall red Flamingo as envisioned by artist Alexander Calder. If you walk east a few more blocks, you will run into the bronze Lions of Michigan Avenue guarding the entrance of the Art Institute. Go just a bit further to take in the vast expanse of blue that is Lake Michigan, one of the five Great Lakes that collectively make up the largest body of freshwater on the planet. Now, follow me to the other side of the world, where you are more likely to see a flamboyance of pink flamingos flying over a pride of dozing lions. Welcome to the African Great Lakes.

Beyond being our Great Lakes counterpart, this region of East and Central Africa has been a focal geography of MacArthur’s Conservation and Sustainable Development program—part of our freshwater conservation strategy, along with the tropical Andes of South America and the greater Mekong basin in Southeast Asia. The Great Lakes Region of East and Central Africa is one of the most important yet ecologically threatened regions on the continent: a quarter of the planet’s freshwater supply is found in Lakes Malawi, Tanganyika, and Victoria alone, and together the lakes hold 10 percent of global fish species. Moreover, nearly 300 million people rely on the lakes for food, energy, drinking water, crop irrigation, and transport. Within the next 25 years, that population is expected to double, further burdening a water supply that is already threatened by climate change, growth of industry and agriculture, as well as regular droughts interrupted by periods of extremely heavy rainfall.

The Lake Kivu and Rusizi River catchment, where Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo meet, faces all these issues in addition to high elevation. This dramatic landscape, characterized by rugged mountains and steep slopes, in tandem with climate change-induced extreme weather events, is prone to severe soil erosion, flooding, and landslides. This further reduces food and energy security for local communities and increases pressures on high-biodiversity ecosystems that are home to species like the endemic L’Hoest monkey or the colorfully crowned Ross’s turaco.

Ross's turaco

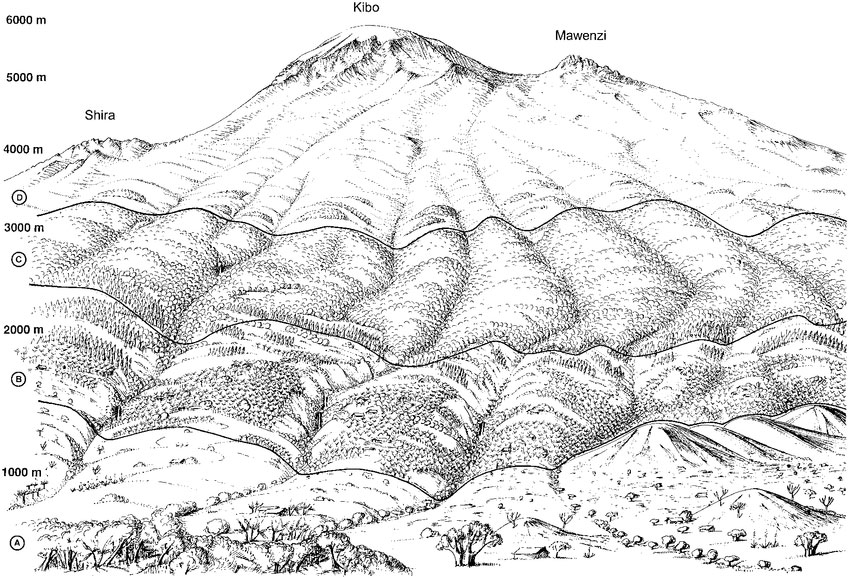

BirdLife International, with support from MacArthur, undertook a risk assessment in order to better understand the ways in which climate change would impact its work in the Lake Kivu-Rusizi River area. With climate adaptation top of mind, BirdLife developed a concept formally titled Climate Resilient Altitudinal Gradients, or CRAGs. Altitudinal gradients—landscapes with at least 1,000 meters of altitude change—are especially vulnerable to extreme climatic events, such as heavy rains, which are predicted to be more frequent in the future. The idea behind CRAGs is to help reduce harm and enhance beneficial impacts of climate change. For example, if altitudinal gradients are properly maintained through careful watershed management and smart agricultural practices, excess rains can be used to offset water shortages during droughts and reduce soil erosion—and the subsequent loss of soil fertility.

Courtesy of Andreas Hemp

Example of altitudinal gradients – every additional 1,000m above sea level presents different ecological characteristics.

Over the past five years, BirdLife has worked with local community cooperatives in Rwanda and Burundi to collect samples from various locations throughout the watershed, starting high in the mountains and ending down by the lakes, to find the most vulnerable erosion hotspots. This offered citizen scientists the opportunity to understand the CRAGs methodology and participate in fieldwork. Following data collection, BirdLife and community representatives codeveloped site-based interventions such as terracing steep slopes, promoting zero-till agriculture, agroforestry, and mulching. Local knowledge and scientific findings enhance climate and livelihoods resilience as well as climate-adaptive land management benefits, ecosystem services, and biodiversity.

These approaches are helping the 1,000 farmers affected by erosion and 1,500 fisherfolk affected by sedimentation, landslides, and floods. Downstream, the improved water quality benefits the 10,000 clients of three micro-hydropower units and the Gihira water treatment plant on the Sebeya River. Additionally, improved land management will minimize habitat degradation that could block the upward movement of plants and animals in response to warmer temperatures at lower altitudes.

Another way BirdLife is addressing the need for climate adaptation and sustainable land use is by partnering with Wildlife Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund for Nature in the Trillion Trees campaign. Trees are a nature-based solution vital to reducing carbon in our atmosphere—a major contributor to global climate change—mitigating erosion, providing habitat for wildlife, supporting local communities by providing sustainable incomes from timber and non-timber products, providing ecosystem services such as water regulation and supply, and making landscapes more resilient to climate change.

As climate change increases the frequency and intensity of extreme weather and climate events, functioning ecosystems can provide protection by stabilizing land and water and buffering climatic impacts and hazards. Through strategic climate adaptation planning, like those implemented by BirdLife International, we can conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services that help people adapt to the adverse effects of climate change.

Landslides in rural Bujumbura, Burundi. © Théodomir Rishirumuhirwa