The Resurrection Project creates healthier communities by investing in affordable housing, engaging in community outreach and organizing, and offering residents immigration legal aid, financial counseling, and youth programming.

Raul Raymundo says he has seen the Pilsen neighborhood on the Southwest Side go through stages of being good, bad, and ugly… then good again. The early good days came during his childhood in the early 1970s, when increasing numbers of Mexican immigrants like his family moved into the formerly Eastern European neighborhood.

The “bad and ugly” stage soon followed, as city officials and commercial investors seemed to ignore the increasingly Latino neighborhood. Trash piled up, schools were crowded, buildings deteriorated, and crime was high.

But then Pilsen experienced a renaissance, and Raymundo helped lead it. In 1990 Raymundo co-founded The Resurrection Project, bringing together Catholic churches to invest in affordable housing, social services, and community organizing. They helped the community define its needs and ensure those needs were met.

“We did it from the perspective of what are the tangible and intangible assets,” Raymundo said. “The tangible are the churches, the geographic location, access to transportation, community institutions like the National Museum of Mexican Art. The intangible culture, language, values, the spirit of the community are also assets we were able to build on. That to me was important, to change the psychology of the neighborhood that it’s not a bad place to live, it’s the place you want to live.”

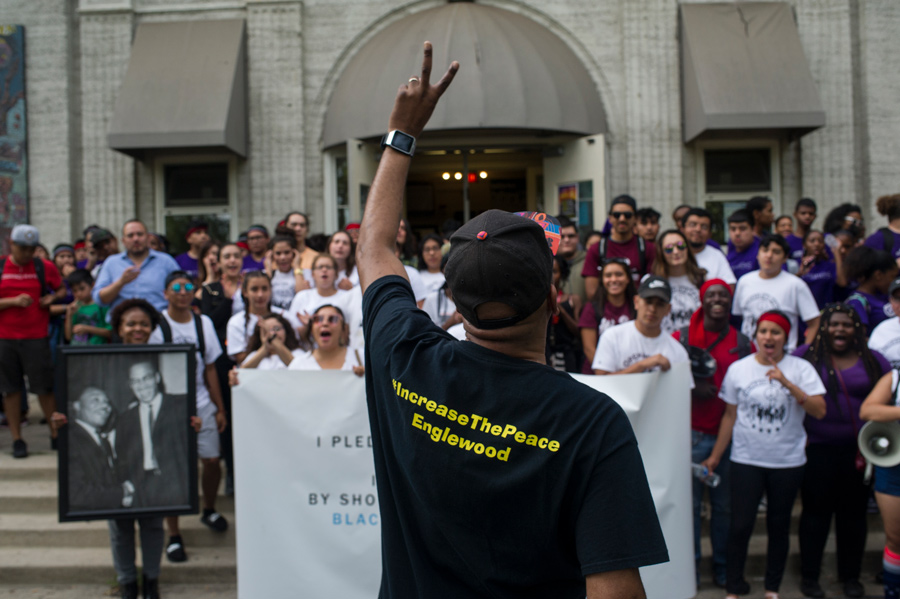

Today, The Resurrection Project works in other neighborhoods in the city and suburbs and has leveraged more than $500 million in community investments, and it provides housing to more than 800 families. It also offers economic development opportunities, housing, immigration legal aid, financial counseling, and youth programming. It hosts summer night campouts on “hot blocks” with high rates of gun violence as a way to unite local communities and promote peace, and it partners with several other agencies to offer early childhood education, health services, leadership development, and other social services.

Through its work in creating the Second Federal credit union, The Resurrection Project also provides mortgage assistance and low-interest loans helping immigrant customers buy their first homes, save their houses from foreclosure, and pursue their financial goals.

The impact of The Resurrection Project ripples well beyond the borders of its focus areas in Pilsen, Back of the Yards, Little Village, and suburban Melrose Park. Several of Chicago’s civic leaders cut their teeth or broadened their skills working at The Resurrection Project or with Raymundo.

About 15 years ago Edgar Ramirez was looking for ways to make the city a better place. Just out of college, he was inspired by The Resurrection Project’s work in Pilsen and asked Raymundo to “give him a chance” to join the team. Raymundo assigned Ramirez a daunting task – to start a new initiative in one housing development in the suburb of Highwood, offering a range of services to the immigrants there.

As Ramirez explains it, “The Resurrection Project model of organizing emphasizes self-interest of both individuals and the community. It’s relationship-building and developing community support and interest along a singular idea: engaging people in a critical conversation about what they'd like to see in their community.”

Today, Ramirez is president and CEO of Chicago Commons, which offers high-quality early childhood education at centers it operates, including two owned by The Resurrection Project in Pilsen and Back of the Yards.

Sylvia Puente came to The Resurrection Project in 1997 from the Latino Institute. While she already had a prominent track record, her work had been primarily “as a talking head,” she says, proposing and advocating for policy. At The Resurrection Project, as director of new community initiatives, she had the chance to do hands-on work.

“I got to mentor community leaders, start a family engagement program, understand child development,” said Puente, who is now executive director of the Latino Policy Forum. “We opened an employment program, and on the first day over 100 people showed up looking for jobs.”

Other Chicago leaders who have worked at The Resurrection Project include Juan Salgado, former CEO of the Instituto del Progreso Latino and now chancellor of the City Colleges of Chicago; and Susana Vasquez, now associate vice president in the University of Chicago’s Office of Civic Engagement.

Asiaha Butler is a native of Englewood, the low-income mostly African American neighborhood just east of Back of the Yards. About a decade ago she dedicated her life to changing the image of Englewood. Butler never worked at The Resurrection Project, but Raymundo recognized the similarities between her work and his model. He frequently meets with Butler to brainstorm, and The Resurrection Project identified a donor whose support enables Butler to dedicate herself full-time to the Residents Association of Greater Englewood and related community organizing.

“In terms of community ownership, the pillars The Resurrection Project stands for could be applied to any community,” Butler says. “How do you have both advocacy and development and make sure that communities feel their worth, their value? Those are some of the principles that Raul always exhibits and shares.”

Raymundo says he is grateful for all the talented and passionate leaders who have come through The Resurrection Project.

“I learned early on that it was very important to build an environment of learning, an environment where people were challenged, where people related to each other,” he says. “That allowed great people to come work here, adding their finger prints to our mission. Many of them were early in their careers. In some cases our naïveté was our strength – we just always found ways to get things done.”

MacArthur has provided $2.37 million in support to The Resurrection Project since 1998, including a $1 million institutional support grant in 2017.