Live Free Chicago’s programs work with churches to help people returning to communities after incarceration, prevent gun violence and incarceration, and get communities involved civically.

When Chauncy Stockdale was released from prison after eight years of incarceration, the world he returned to felt unfamiliar.

He was confronted with strained family dynamics. His background with the criminal justice system made it challenging to find a job. Even everyday tasks like grocery shopping overwhelmed him.

For a month, Stockdale attended job fairs and networked with employers. He made little progress until, during one job rejection, the employer told Stockdale about the yearlong Decarceration Fellowship that trains formerly incarcerated individuals in community organizing and equips them with practical workplace skills. After connecting with coordinators, Stockdale was added to the cohort.

“In the Fellowship, we see each other with empathy, and we help each other succeed.”

“When I see another Fellow’s face, I see a friend,” he said. “A lot of times in our neighborhoods, if you don’t know someone, you don’t reach out. But in the Fellowship, we see each other with empathy, and we help each other succeed. I don’t have to figure everything out on my own.”

Building Power Through Congregation

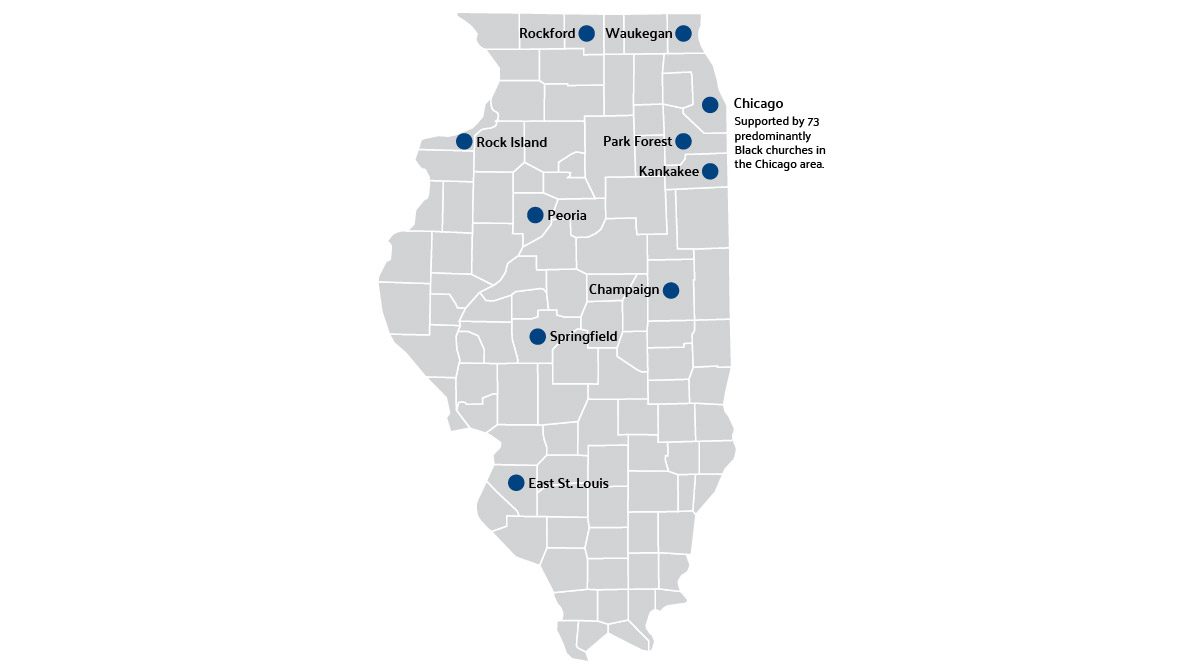

The Decarceration Fellowship is run by Live Free Illinois, a statewide organization seeking to prevent gun violence and incarceration by mobilizing Black congregations. In Live Free’s Chicago location alone, the organization works with more than 70 predominantly Black churches. Another 10 Live Free branches across Illinois work with faith-based communities from East St. Louis to Waukegan.

Live Free Illinois has Community Human Resource Networks (CHRC) across the state, that provide counseling, education, and support to those affected by gun violence and incarceration. In Chicago, Live Free's CHRC is supported by a network of 73 predominantly Black churches. View accessible data ›

Since its founding in 2017, Live Free Illinois has trained hundreds of congregations in community organizing. Last year, the organization launched a chain of Community Human Resource Networks that provide counseling, education, and support to people directly or indirectly affected by gun violence and incarceration.

Since its founding in 2017, Live Free Illinois has trained hundreds of congregations in community organizing.

In the short-term, Live Free Illinois measures success by the number of faith communities mobilized and the number of laws and policies reformed. Long-term success will be measured by transformed, thriving Black communities, said Rev. Ciera Bates-Chamberlain, founder of Live Free Illinois.

“I really wanted to organize Black churches and center Black voices in a way that respected our dignity, our agency, our imagination,” she said. “I created Live Free to do just that. It’s one thing to have Black stories and voices at the table, but it’s another thing when Black people are leading the policy.”

Another ongoing project is Live Free’s advocacy of automatic record relief, which erases an individual’s criminal record without requiring action by the individual. Current state law requires individuals who have completed their sentences to work through an often expensive, lengthy court process to obtain record relief on their own.

Fellowship cohort member Gerald Johnson places a piece of dissolvable paper into “Sea of Forgetfulness.” On the piece of paper, members write what they plan to release as they let go of the past and begin their journey. Credit: Live Free

For the estimated 2.2 million people in Illinois eligible for record relief, automating the process would be life changing, Bates-Chamberlain said. It can open up access to basic needs like renting an apartment or getting a job.

Beyond those efforts, Live Free Chicago and Live Free Illinois – part of the national Live Free organization – are advocating for the establishment of a City of Chicago Office of Gun Violence Reduction and improved clearance rates of crimes, especially homicides.

Live Free also offers training on strengthening congregations’ social justice ministries, increasing voter turnout, investing in community economic development, and divesting from discriminatory companies.

The national organization has granted millions of dollars to community groups and provided training and coaching to thousands of leaders to support peace. “The return on these investments,” the national Live Free website states, “has been billions of dollars in public funding for CVI [Community Violence Intervention] initiatives and key criminal justice reforms throughout the country.”

Many of those reforms, such as expanded background checks for gun buyers, $11 billion for mental health services, and $2 billion for community-based violence prevention initiatives, were in the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. Another reform occurred in 2021, when the Black & Brown Consortium—Live Free is a member—won $6 billion in federal, local, and state commitments for CVI.

Reshaped Self-Perception

Stockdale was one of 15 Fellows—all formerly incarcerated men and women—in the Fellowship’s second cohort. While he joined that cohort after his release, most Fellows participated for the first three months while still incarcerated. Once they returned home, nine months of reentry support followed.

In group sessions, participants hear from guest speakers, engage in one-on-one networking, and develop concrete skills such as professional email etiquette and resume-building.

They also participate in civic activities, including a Lobby Day in Springfield, Illinois, where they met with lawmakers and learned how to engage civically with their home communities. The second cohort of Decarceration Fellows graduated in the summer of 2025.

The Fellowship led Stockdale to a career supporting his community. Midway through the program, he began working part-time as a program coordinator with the Illinois Alliance for Justice and Reentry, where he helps incarcerated individuals build support networks and plan for their future beyond prison.

Instead of a barrier, his background became a unique asset.

Stockdale credits the program with reshaping his self-perception. Before the Fellowship, he said he did not imagine working in reentry or community advocacy. The program’s structure and support prompted Stockdale to view himself as more than someone reentering society. Instead of a barrier, his background became a unique asset. Stockdale saw that he could be a leader and valued community contributor.

In addition, the Fellowship focused on workplace skills and created a rare community where personal concerns could be addressed alongside professional ones. Each session allowed room for conversations about housing, mental health, and family dynamics — topics that often shape the success or failure of reentry efforts. Stockdale said that holistic support was critical, particularly when the pressures of returning home felt isolating.

Members of the Decarceration Fellowship meet at the annual Welcome Home Dinner held for each new cohort. Credit: Live Free

“When people reenter society, a lot of people say, ‘You’re supposed to have it all together,’” Bates-Chamberlain said. “But it’s hard to make that transition, and we’re all human. You need to have a space where you feel like you can open up and not feel like someone will judge or laugh at you. Live Free is that safe space.”

A year after his release, Stockdale said his work is just beginning. He hopes to return to Live Free as a guest speaker for the next cohort of Decarceration Fellows, offering mentorship and support to individuals navigating the reentry challenges he faced.

For Stockdale, the journey is personal and part of a broader effort to strengthen his community by preventing incarceration and assisting people it affects.

He said he wanted to “come home and bring change and community to other people — for the next generation. Because we all play a role in cleaning our neighborhoods up. So, our kids can play safely in the front yard again.”

Since 2021, MacArthur has provided $335,000 of support to Live Free Chicago to operate the Decarceration Fellowship and convene faith leaders and residents to develop a statewide agenda on criminal justice reform.