Scientists and meteorologists use attribution science to identify and keep the public informed on how climate change causes weather catastrophes.

Looking over the blackened earth, scorched trees, and incinerated remains of his home in the southeastern Blue Mountains, Michael Greene suddenly grasped the true origins of the catastrophe that made this summer Australia’s cruelest.

“I’ve been thinking to myself, ‘I ’m a bushfire victim,’ but after a while I started to get a realization,” Greene told a TV news crew early this year. “I thought, ‘No, I ’m not; I ’m a victim of climate change. ’ ”

A few weeks later, scientists using sophisticated climate models confirmed what he and many others suspected. Climate change played a major role, making the hazardous conditions that led to Australia’s monstrous blazes at least 30 percent more likely than they would have been without human-caused global warming.

That was the conclusion of researchers at World Weather Attribution, an international consortium that analyzes extreme weather events in real time. It is one of many groups advancing a subfield of climate science known as extreme event attribution, which quantifies climate change’s impact on specific weather-related events. The research has ushered in a new era of journalism, helping advance the public’s understanding of climate change’s immediate impact.

A report from World Weather Attribution concluded that human-caused climate change had an impact on Australia’s wildfires.

“If people aren't paying attention now, I don’t know when they ’re going to pay attention,” said meteorologist Angie Lassman of NBC 6 in South Florida. She was able to persuade station managers to send her and a producer to Australia for “Unprecedented,” a five-part mini-documentary on the fires.

Her interview with Greene is among several stunning moments in the series underscoring how attribution studies have shifted perspectives.

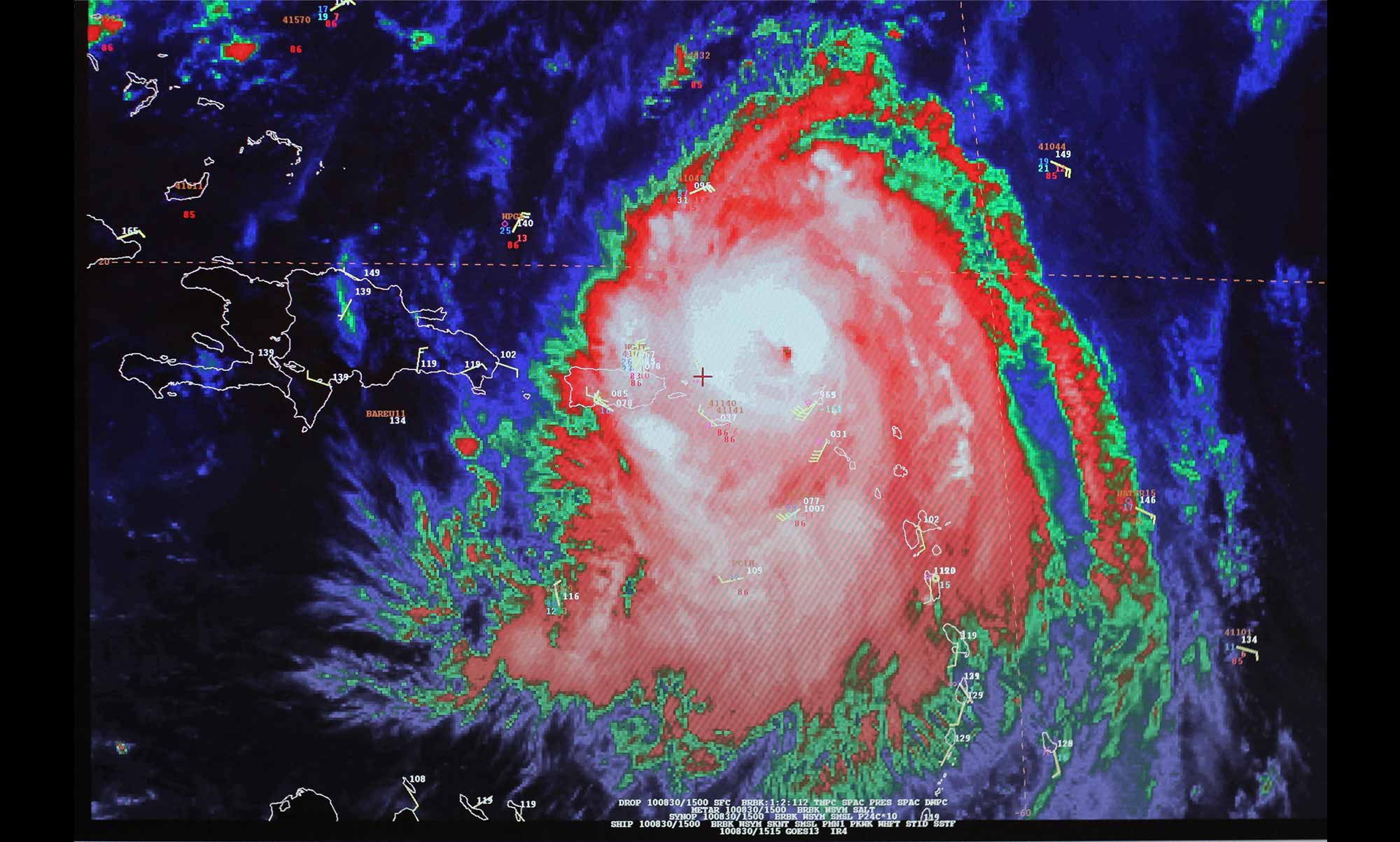

For years, an important question after a cataclysmic storm was whether climate change played a role. Now, attribution science answers the question, estimating how much climate change influenced the probability or intensity of a specific flood, hurricane, wildfire, drought, or other event. That work used to take months. Today, scientists can do it in near-real time, while the drama is still fresh in people’s minds.

Made possible by rapidly advancing computer processing power and climate models, the science has evolved since a 2004 study found climate change at least doubled the likelihood of the 2003 European heat wave, which contributed to the deaths of more than 70,000 people.

Put simply, scientists compare events against long-term data and models of a climate without human deposits of greenhouse gasses. The experts can weed out factors such as urban development, which can exacerbate flooding, to be sure they are measuring only the effect of climate change.

“Before attribution science, the language scientists and journalists used was often weak or evasive,” said Benjamin Strauss, chief scientist and CEO of Climate Central, a nonprofit helping journalists access and report on climate research. “It was always, ‘Well, what we ’re experiencing is consistent with climate change, but I can ’t really speak to the specific event.’ There was an excuse in it.”

Now TV meteorologists can tell viewers, for instance, that excessively hot days like the one they may be experiencing that very day have become two or three times more likely because of climate change.

“Attribution science lets us put climate change in the present tense,” Strauss said.

This rapidly developing science is quantifying impacts in surprising ways.

A 2013 study by Rutgers University scientists found human-caused sea-level rise extended the reach of Superstorm Sandy by 27 square miles, affecting an additional 83,000 people in New Jersey and New York City. Research presented in 2014 showed that the broader impact elevated damage from the 2012 disaster by an extra $2 billion in New York City alone.

A 2018 study of Hurricane Florence, which struck the Carolinas that year, specified that 11,000 homes of the total 51,000 destroyed would have been spared if global warming had not been a factor.

NBC 6 meteorologist Angie Lassman, who traveled from South Florida to Australia to report on its bushfires and their link to climate change, relied on attribution science.

“I’ve had viewers thanking me for telling this story, from realtors, to fishermen, to people who have to try to get their kids to school on days when we have sunny-day flooding,” said Lassman of NBC 6. “When you have solid ways to attribute that this is being influenced by climate change, people pay attention.”

She is among 800 TV meteorologists and 400 other journalists, who receive weekly updates from Climate Central with data, ready-to-air graphics, and other material to help shrinking newsrooms strengthen climate reporting.

Evidence is emerging that meteorologists using attribution science are shifting opinions. After a meteorologist aired segments linking climate change and the weather in a conservative South Carolina media market, researchers with George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication found viewers’ concern about climate change grew.

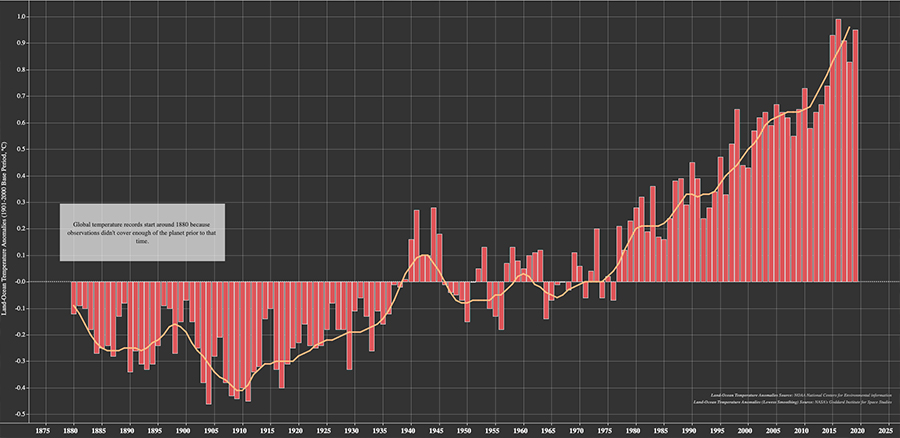

Another initiative, ClimateSignals, synthesizes attribution research and other analyses to highlight the strongest connections between climate change and emerging impacts for journalists, using techniques such as easy-to-understand graphics, data visualizations, and fact sheets. One recent example looks back at the hottest decade on record and explains how climate change is entirely responsible for planetary warming and is directly responsible for most individual heat records.

Research from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA shows that 2009 to 2019 was the hottest decade on record.

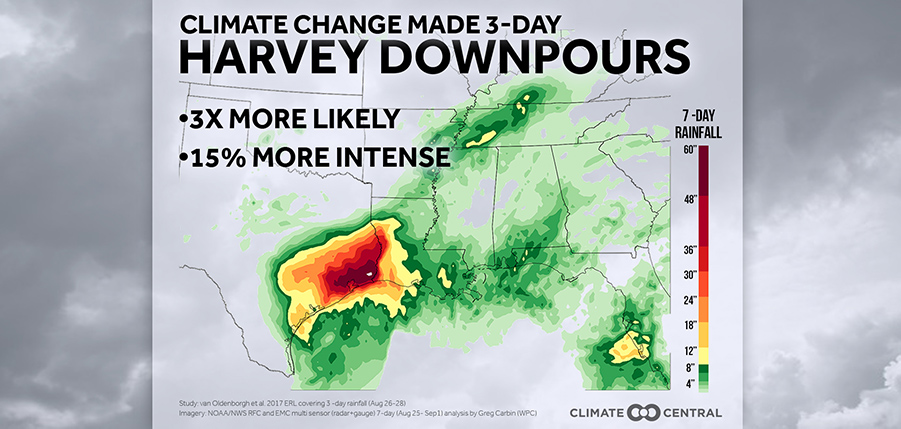

Supported by such data, reporters and meteorologists are holding leaders accountable. After Texas Governor Greg Abbott resisted acknowledging a connection between climate change and Hurricane Harvey, meteorologists at KXAN in Austin set the record straight on air, citing abundant attribution research done within days of the 2017 storm—the second-most costly hurricane in U.S. history.

“Studies found that were it not for man-made climate change’s contribution, rainfall in Harvey could have been 38 percent lower,” one of the meteorologists, David Yeomans, told viewers.

“It comes down to making it relatable,” he said in an interview. “If I can stand in a neighborhood and tell viewers this part of town would not have flooded if it weren’t for climate change, that’s a really powerful thing.”

Using attribution science, this map from Climate Central shows impact of climate change on Hurricane Harvey.

MacArthur has provided $3.5 million in support to Climate Central since 2015. Climate Signals is a project of Climate Nexus, which has been awarded $20 million in general operating support since 2016.