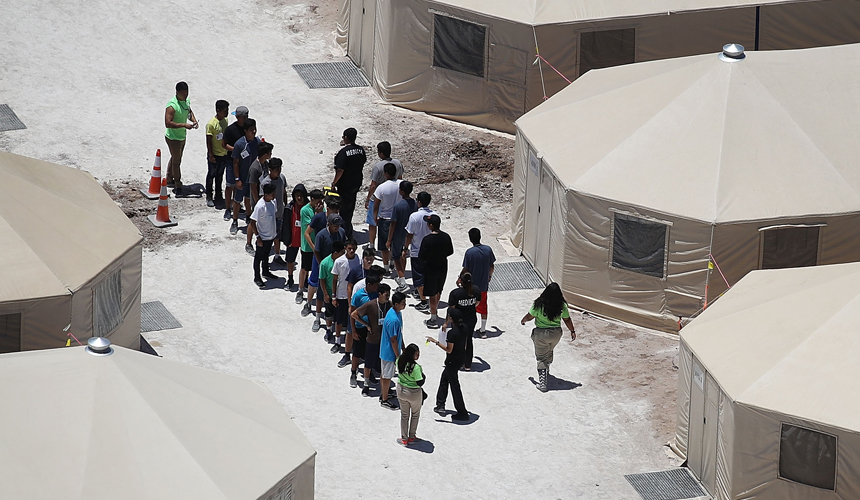

When I began this work in 2004, 8,000 unaccompanied children arrived at the border each year. Last year, the number of children crossing the border – all on their own – reached 50,000. Most of the children are coming from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, countries experiencing unrelenting violence, poverty, and hunger. It’s a humanitarian crisis of major proportions.

© Getty Images

Before founding the Young Center, I worked in children’s rights, not immigration. I was shocked to learn that when it comes to immigrant children, there is no “best interests of the child” standard in immigration law and no mention of safety when a child was at risk of deportation. My charge was to create a program to advocate for the best interests of unaccompanied children, all of whom were being held in detention.

We relied on the Convention on the Rights of the Child and each state’s best interest standards in child welfare law to craft our arguments. We found that immigration judges, asylum officers, even some enforcement officials wanted information about a child and his or her family before making a decision about placement or release. Many were clearly uncomfortable making a decision about returning a nine-year-old to his or her home country without knowing to whom they would return, whether there was a parent in the picture, or whether the child would be safe. In 2008, we had the first of many small victories. In the waning days of the Bush Administration, Congress reauthorized the federal anti-trafficking law, with a new provision giving the federal government authority to appoint independent child advocates to represent the best interests of unaccompanied children. Our child advocates are now requested so often that we have waiting lists at every one of our sites.

© Getty Images

In 2012, officials at the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice asked the Young Center to prepare a written guide for determining each child’s best interests—even without a legal mandate for agencies to do this. The MacArthur Foundation supported this project. Jennifer Nagda, the Young Center’s Policy Director, and I spent the next two years talking with senior officials in various government agencies to collect their best ideas. It turned into a three-year project, and, when we finished, each of the contributing agencies pledged to put the resulting Framework for Considering the Best Interests of Unaccompanied Children into practice.

The arc of justice bends slowly. We now have special courts for children and special judges assigned to hear children’s cases. The Justice Department created a training program for judges presiding over children’s cases. Our lawyers are the trainers. Judges, asylum officers, and enforcement officials accept best interests reports as part of a child’s immigration case. In 2015, we started working with the Department of Homeland Security to create a special unit to examine cases in which children were denied asylum but either had no family to return to or faced danger if they returned. This unit would investigate whether the child would be at risk if repatriated, consider the child’s best interests, and decide whether to exercise discretion and halt deportation.

Then came the 2016 election and an end to our discussions with senior agency officials. Since January 2017, there has been no shortage of challenges, most recently family separations, but we continue to make progress on a case-by-case basis, with individual judges, with government attorneys, and with immigration officials.

© Getty Images

All along, our concept has been to change practice, then written policy, and eventually the law. Our immediate focus is to change the way we treat children who arrive on their own or who are separated from their families. In a recent case, we were appointed to advocate for two young children, ages three and five. Their mother had been deported and the immigration judge had to decide whether the children should remain in the United States or return to their mother’s care. The judge looked to the Young Center Child Advocate and asked, will they be safe, who will they live with? We had conducted an investigation in the children’s home country and had information in hand. We strenuously urged that it was in the children’s best interests to be reunified with their mother. When challenged, the judge said, “Why do we have a Child Advocate if we’re not going to follow their best interests recommendation?”

We now have eight offices across the country. We’ve grown from a staff of one to more than 50, an assortment of attorneys, social workers, volunteer coordinators, and paralegals. We continue to advocate with shelter directors, immigration officials, government attorneys, and immigration judges who have the authority to decide whether a child will be returned to his or her home country or granted protection in the United States. Every day we submit recommendations, and each time they become more accustomed to considering the best interests of the children before them.

Between 2012 and 2018, MacArthur awarded five grants totaling more than $995,000 to the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights.