About Cameron's Work

Cameron Rowland is an artist making visible the institutions, systems, and policies that perpetuate systemic racism and economic inequality. Rowland’s research-intensive work centers around the display of objects and documents whose provenance and operations expose the legacies of racial capitalism and underscore the forms of exploitation that permeate many aspects of our daily lives.

In a 2016 exhibition, 91020000, Rowland presented a series of objects—including courtroom benches, desks, and leveler rings for manhole openings used in road construction—manufactured by New York State prison inmates, who are paid $0.10 to $1.14 an hour. Rowland also documents the procurement of the items from Corcraft, the market name for the Division of Correctional Industries within the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. Corcraft sells the items at below market value to government and nonprofit agencies, meaning, in effect, that such agencies are complicit in perpetuating injustices of the criminal justice system. In a detailed and carefully researched essay that accompanies the exhibition, Rowland traces the history of prison labor programs to the convict lease labor system that developed in the post–Civil War South and argues that the American prison system has descended from slavery. Rowland has devised various ways to implicate and activate the financial systems that historically profited from the oppression of black Americans. Disgorgement (2016) consists of a purpose trust established by Rowland to contain 90 shares of stock from the Aetna company, which profited from the provision of insurance to slave owners for their human property. In the event that federal financial reparations are granted to African American descendants of slaves, the accrued value of the trust will be paid to the U.S. federal agency in charge of distributions.

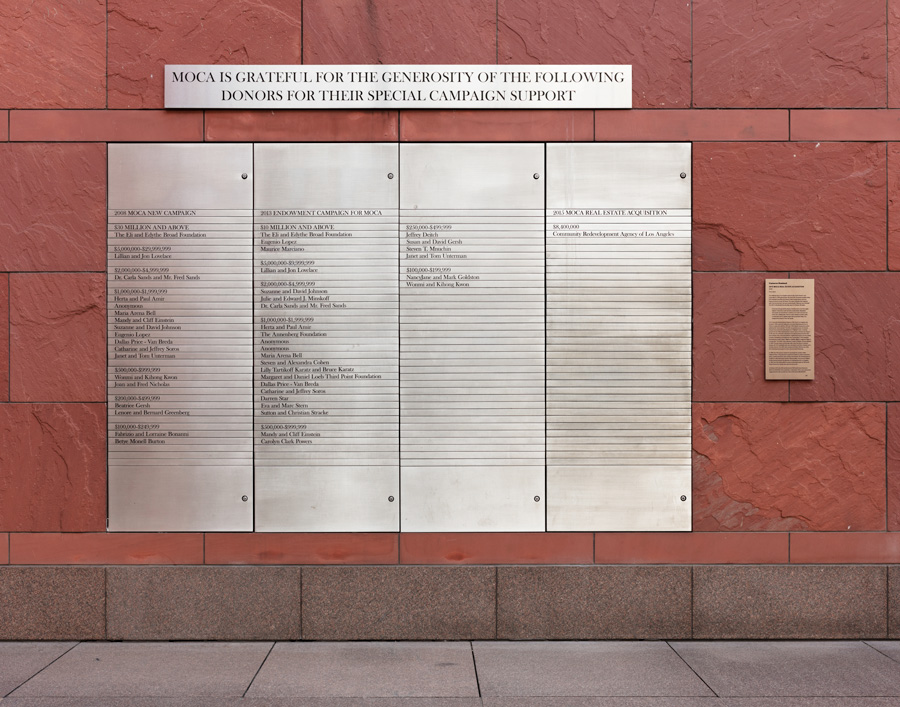

Rowland’s institutional critique extends to the art world as well. The first work in Rowland’s 2018 exhibition D37 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, entitled 2015 MOCA REAL ESTATE ACQUISITION, takes the form of a donor plaque accompanied by a narrative accounting of how the museum is the direct beneficiary of practices of redlining based on racial discrimination to suppress property values. Rowland is providing new models for art to engage with justice and, in the process, throwing into question some of the basic premises of Western art, including the edifying power of the aesthetic object and the autonomy of the work of art itself.

Biography

Cameron Rowland received a BA (2011) from Wesleyan University. Rowland’s work has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions at such venues as the São Paulo Biennial, the Whitney Museum of American Art, Vienna Secession, Artists Space, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Rowland’s work is represented in public collections including those of the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Featured Work

Cameron Rowland

2015 MOCA REAL ESTATE ACQUISITION, 2018

Donor Plaque

The redlining map of Los Angeles drawn by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1939 gave Bunker Hill, block D37, the lowest possible rating. D37 extended from West 4th Street to West Temple Street, and from Figueroa Street to South Hill Street. The report indicated that residents were “low-income level” and were predominantly “Mexicans and Orientals.” The HOLC’s Residential Security Map report for Bunker Hill states:

It has been through all the phases of decline and is now thoroughly blighted. Subversive racial elements predominate; dilapidation and squalor are everywhere in evidence. It is a slum area and one of the city’s melting pots. There is a slum clearance project under consideration but no definite steps have as yet been taken. It is assigned the lowest of 'low red' grade.

The Community Redevelopment Agency of the City of Los Angeles was formed in 1948 under the California Community Redevelopment Act of 1945, in conjunction with the 1937 and 1949 federal Housing Acts, which authorized its “slum removal.” The CRA was granted powers of eminent domain to be used in the redevelopment of “blighted” areas. A primary purpose for the CRA’s redevelopment projects was to increase tax revenue for the city. One of the first redevelopment projects proposed by the CRA was in Bunker Hill, on the basis that the neighborhood spent more tax dollars on police, firefighting, and healthcare than it generated. A CRA pamphlet promoting the project stated, “Blight is a liability, Blight is malignant, Blight is a social peril.” The CRA’s “slum clearance” project in Bunker Hill was adopted in 1959. Through seizure and through sales under the threat of eminent domain, all 7,310 residential units were demolished and their residents were forcibly removed. The CRA’s slum clearance in Bunker Hill was one of the first redevelopment projects to rely on tax increment financing.

In 1980, the CRA issued a request for proposals for a project called California Plaza. Proposals were required to include an outdoor pedestrian plaza, a parking structure, and a modern art museum. The winning group of architects called themselves Bunker Hill Associates. The museum outlined in this proposal became The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. In 1983, the CRA offered MOCA a lease on the land located at 250 South Grand Avenue for a ninety-nine- year term at no rent.

In October 2015, the CRA sold the land at 250 South Grand Avenue to MOCA for $100,000. One month later, in November 2015, a tax assessment triggered by the sale recorded the value of the land at $8,500,000.

Published on September 25, 2019